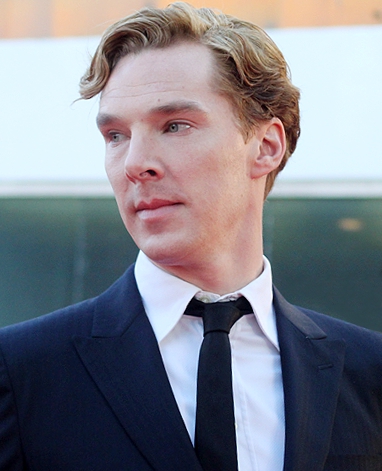

Benedict Cumberbatch, at the London premiere of “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy” in September 2011, stars in the Oscar-buzz worthy “The Imitation Game” as mathematician Alan Turing.

Thanks to Marshall Fine, critic-in-residence at The Picture House in Pelham, I had the opportunity recently to preview “The Imitation Game,” which has “Oscar nods” written all over it, deservedly so. It’s a superbly crafted film about a story that resonates in our own time, acted with the kind of understated emotion that is the hallmark of British performance by a cast that includes Benedict Cumberbatch (“Sherlock”) and Keira Knightley.

The film, which opens Nov. 28, tells the story of Alan Turing, the mathematician who cracked Germany’s Enigma Code during World War II by creating a machine that was the forerunner of the computer, saving millions of lives in the process (although that, we shall see, was complicated).

Turing was a man ahead of his time in many ways. Today he’d be a gay Bill Gates or Steve Jobs. Instead he was a closeted social misfit – taunted mercilessly at prep school in the savage way that belongs exclusively to children and later prosecuted when his homosexuality was uncovered after the war. Forced to choose chemical castration in lieu of a prison sentence, he committed suicide in 1954 at age 41 – one of 49,000 men prosecuted for homosexual acts in England between 1885 and 1967. In 2013, Turing was pardoned by Queen Elizabeth II – which still implies he did something wrong to begin with.

What he did was try to live out his identity. Faced with the loss of that identity – the female hormone therapy sapped his mind as much as his maleness – he relinquished his life altogether.

In a sense, he was the perfect person to serve as a cryptographer ostensibly “working in a radio factory” during the war. As a closeted gay, Turing was already good at keeping secrets. “The Imitation Game” is what he called the computer. But life is the real “Imitation Game,” as not only he discovered. There was fellow code-breaker Joan Clarke (Knightly), “a woman in a man’s job” unfazed by being his beard had she become his wife; the counter Soviet spy within the team; and the code-breakers themselves, who had to choose how to use the information they obtained once the code was cracked so as not to tip their hands to the Germans and thus in effect got to decide who lived and who died.

Everyone was pretending to be what he wasn’t. But then aren’t we all?